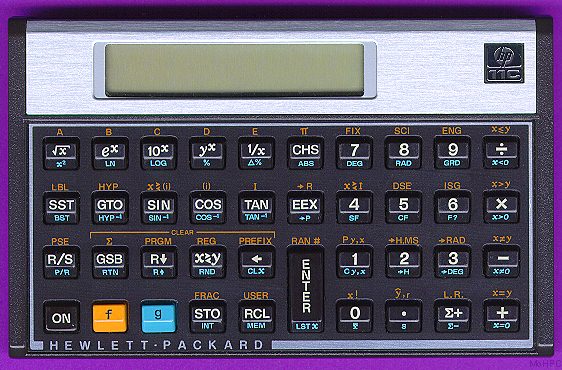

I must have been asleep in the past six months or so because I just found out that it’s back, for sale right now, and it is pretty darn good. Hewlett-Packard have done a wonderful thing and have put into production a replica (or reproduction) of the wonderful HP-15C calculator. The calculator that many credit with getting them through engineering school and then through their careers. It is, to my mind, the finest engineering calculator ever produced.

Though made in China now, rather than the US or a few other countries like the original HP-15C, the reproduction, called the Limited Edition by HP, seems very well made and almost identical to the original. It comes in a nice presentation box along with a printed owners manual that seems to be a reprint of the original.

Here is the new one next to an original in good condition. The only main visual difference is that the new one’s screen has a greenish tint to it while the original is gray (that doesn’t really show in the pictures and it is not a big deal).

In operating the calculator, you do notice a slightly different feel with the keys. The LE has slightly flatter keytops and the texture is slightly rougher – that might be just because I am comparing it to an original 15C that has had some use in its 30 year life. The f and g keys also feel a bit wobbly compared to the original but they don’t seem to be as bad on mine as some people found on the first batch that came out. The key action is just as good, or maybe even a little better, than the original. And that is saying a lot. It is a wonderful calculating experience.

As far as I can tell, the LE does everything the old one did, in the same way (except for the diagnostics check), and, because of a new processor, does it much, much faster. I guess there was some price gouging in the Fall, but now they seem to have settled down some. Amazon has it for $129.99, but you can order directly from HP (http://www.shopping.hp.com/webapp/shopping/product_detail.do?storeName=storefronts&landing=calculator&category=HP&a1=Type&v1=Scientific&product_code=NW250AA%23ABA&catLevel=2) for $99.99 with free shipping. I got two and they arrived in just a couple of days.

Any of you who lost their 15C, or want to gently retire theirs, or who always wanted one but couldn’t afford it at the time (me), I highly recommend purchasing an LE. I think it is still the best calculator an engineer can have at his side that can also fit in his shirt pocket.

By the way, this is a great site for all HP calculators: http://www.hpmuseum.org/ The forums are active and filled with interesting calculator nerds – a lot of engineers, in other words.